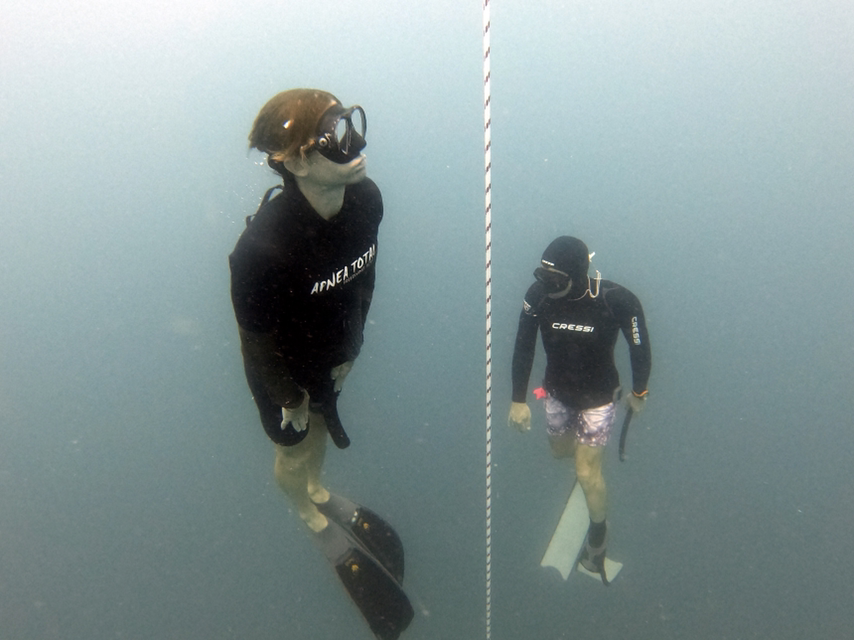

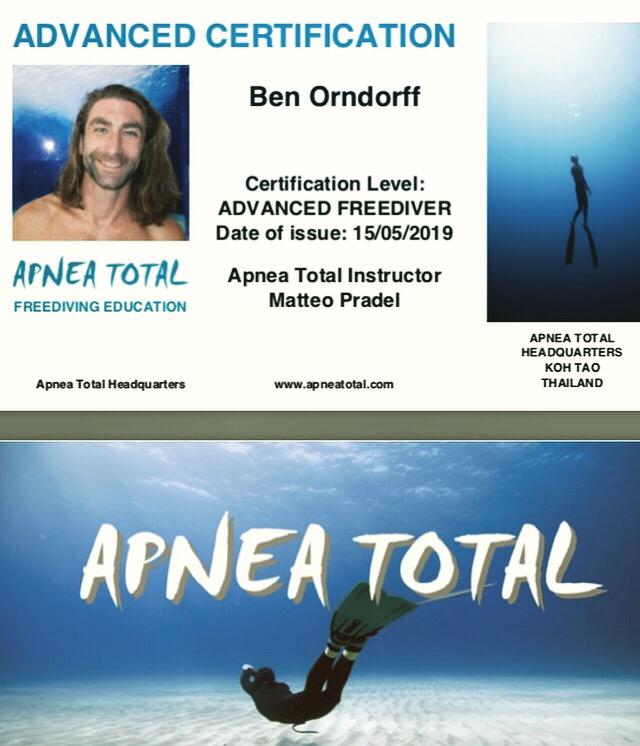

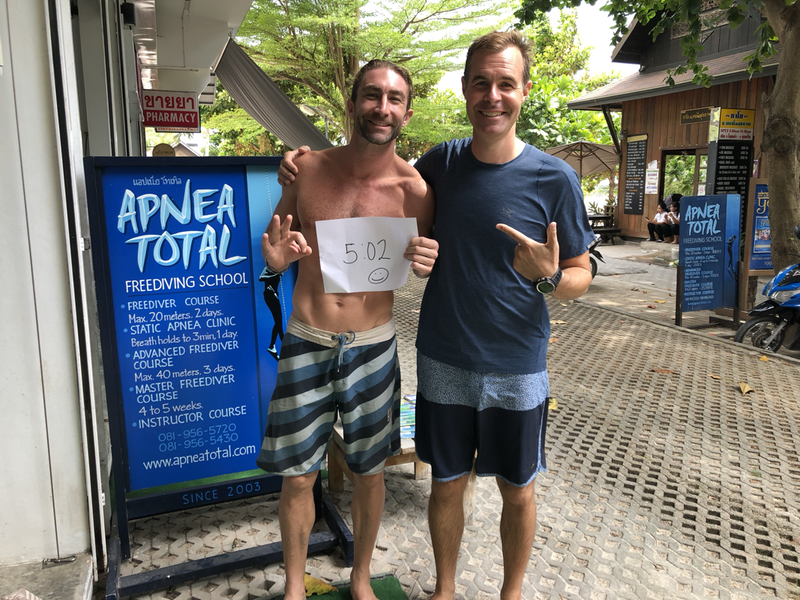

Southeast Asia Travel Video (part 3)Cruising around with new friends The AbyssFalling, perfectly upside down, headfirst into the depths of the open ocean is an unsettling sensation and yet somehow there is an air of a spiritual bliss to it. It’s eerily silent, the surface disappears from view, and you are alone with the abyss. At about 30 feet the air in your lungs has compressed enough that you begin to sink. At this point swimming is replaced by a meditative free-fall to conserve oxygen, allowing the sea to draw you deeper into its cold, dark embrace. Watching the rope in front of me as my only point of reference, I could see that I was accelerating with the rapidly increasing depth. I tried hard to remain calm and avoid thinking about the fact that I was speeding in the opposite direction of the air that I would need to breath soon to not die. Diving the line The pressure on my entire body was unlike anything I had ever experienced. After the first 33 feet, or one “atmosphere” of pressure, my lungs had already halved in size. For every subsequent 33 feet I descended, the force upon my body increased by 15 pounds per square inch. As I cruised past 100 feet, the pressure had tripled and my heart reflexively slowed to around half its normal resting rate. It was only beating 25-30 times per minute. My entire body was essentially operating in slow motion. Returning from the deep "It’s eerily silent, the surface disappears from view, and you are alone with the abyss." As blood began shifting to my thoracic cavity to protect my lungs from the pressure, I experienced a zen-like euphoria that is as renowned and beloved by freedivers as the “runner’s high” is by our terrestrial counterparts. Calm and confident I continued my descent into the darkening water. This was my third and final “deep dive” attempt of the day and I was determined to reach the end of the rope, 115 ft below the surface. To get an idea of what that actually looks like, peer off a balcony from the 10th story of an apartment building and imagine swimming to the ground and then back up. Yeah, it freaks me out too. Out of the haze, the weights at the end of the rope came into focus. Fuck yes! Just a few more feet. My grip closed around the line where it met the weights and my inertia automatically swung my body 180 degrees so that I was now facing straight up the rope. My chest ached as I began the long return ascent, away from the dark nothingness below and back towards the shimmering, sun-kissed ripples far overhead. "...peer off a balcony from the 10th story of an apartment building and imagine swimming to the ground and then back up." By the time I was within the last 50 ft of my ascent the involuntary contractions of my diaphram had begun to intensify. But as uncomfortable as it was, I knew I was still only a little over halfway through my max breath hold. Thanks to the CO2 build-up in my system, the contractions provide a reliable indicator of where I am on my dive. It’s the body’s way of letting you know it’s getting close to time to breath so start heading towards air. Cave tunnel swim-through Rocketing towards the surface, I was joined by my spotter, an Italian freedive instructor named Matteo, who had come down to escort me for the last leg of my dive when blackouts are the most common. Breaching the surface like a whale that had been shot out of a cannon, I expelled the CO2 rich contents of my lungs and replaced it with a massive breath of fresh air. Once I had given my lungs a chance to replenish my oxygen levels, a shit eating grin spread across my face. That was intense but I made it down to 115 ft. It had been a good day. "But as uncomfortable as it was, I knew I was still only a little over halfway through my max breath hold." Hanging out on our float Hanging onto the float, I allowed my thoughts to drift back to my last dive. As my O2 levels had really started to get low I could almost visualize a little engine room mechanic in my head, running around, freaking the fuck out like Scotty from Star Trek, with alarms and red lights flashing, flipping switches to operate my evolutionary “reptilian brain” functions. These switches shunt blood from my extremities to my core, protecting my organs under the increased pressure, slow my heartbeat to decrease oxygen consumption, and release oxygen rich red blood cells from my spleen; naturally occurring blood doping if you will. All that happens automatically in humans to enable us to dive to greater depths for longer. What an awesome, evolutionary, physiological transformation. Science is neat. Advanced Freediving CourseOfficial Freediver Although I’d been spearfishing for years, I decided to make my relationship with freediving official by taking a three day Advanced Freediver Course on Koh Tao Island in Thailand. After my Borneo jungle adventure, heading to the relaxing islands for a few weeks was exactly what I needed. Not only was this an opportunity to hone my technique and get an international certification, it was a chance to really push my boundaries. Having instructors that could rescue me if I discovered my limits in the form of a “shallow water blackout” gave me the peace of mind to see what my body was capable of. "Not only was this an opportunity to hone my technique and get an international certification, it was a chance to really push my boundaries." Learning is fun Day one of the course at the freediving outfitter, “Apnea Total,” was science, theory, and breath holding techniques. It culminated in a “static breath hold” in a swimming pool. After several minutes of controlled breathing to flood my blood with oxygen and flush some CO2, I rolled over into a dead man's float with the instructor in the water next to me. To minimize the amount of oxygen my brain consumed, I avoided normal thoughts and entered a meditative state in which I imagined myself walking through a familiar place. I used my house. Focusing on images, textures, scents, and sounds deep in my minds eye helped me to stretch my breath hold far longer than I thought possible. As my body began to rhythmically rock with the involuntary diaphragm contractions, my instructor Gavin moved my hands to the side of the pool and asked for a finger tap every few seconds to make sure I was still conscious. On my third attempt I pushed myself to hold on longer than the previous two attempts, in hopes of joining the “Five Minute Club.” When I finally raised my face out of the water and gasped for air my chest was screaming and I was so dizzy I felt like I might pass out. It took ten seconds of air-gulping “recovery breathing” before I felt ready to speak. “How did I do?” I huffed. Gavin smiled and showed me his stopwatch. The display read 5:02. Hell yeah. "When I finally raised my face out of the water and gasped for air my chest was screaming and I was so dizzy I felt like I might pass out." Days two and three were spent diving lines; first to 25 meters and then to 35 meters. The freediving shop’s boat took us out to a calm, protected stretch of water where we could set up our freediving floats. The inflatable ring at the surface is attached to a rope with lead weights at the bottom keeping it taut. This allows freedivers to head straight down, avoiding inefficient diagonal or zig-zag descents. The line is also there as a safety mechanism in case of a foot or leg cramp. At depth, cramps can be debilitating and dangerous especially when you are “negatively buoyant” and running out of air. They also are more likely as muscles are forced to work with far less oxygen while swimming towards the surface at the end of a breathhold. Freediving is, as the name would suggest, freeing. Not only can you ditch all of the bulky gear of scuba diving, you don’t have to worry about decompression sickness. The "bends" results when dissolved gases, mainly nitrogen, come out of solution in bubbles and can affect the joints, lungs, heart, skin and brain. The effect upon the joints can force the victim into sickeningly, unnatural contortion postures, thus the ominous moniker. In extreme cases, the bends can be fatal. Scuba divers breathing compressed air must ascend slowly to prevent the bends, whereas a freediver who takes air at the surface can ascend from depth as quickly as they want. Pure freedom. "The effect upon the joints can force the victim into sickeningly, unnatural contortion postures, thus the ominous moniker." ”We don’t have to go home but we can’t stay here.” The final test to get my Advanced Freediver Certification was a simulated shallow water rescue from 50ft. Matteo swam down a few seconds before me and at 50 ft went limp. As I had been taught, I grabbed his right arm and pulled him towards me. Like a ballroom dance move, his lifeless body spun towards me, his back resting against my chest. Sliding my arm under his armpit and up to his shoulder, I bladed my body 90 degrees to give my legs full range of motion and began kicking for the surface with the pasta devouring Italian’s dead weight in tow. Although, it was hard work hauling a body to the surface, it felt like a walk in the park compared to freediving to the end of the line. Experiencing what it feels like to rescue someone in a controlled environment hammers the training into your muscle memory and builds confidence. Attempting a freediving rescue for the first time in a real emergency could be catastrophic. The course was worth every penny. Whale SharkA few days after completing the course I hopped on a freediving “fun dive” boat. This was essentially a small group of us tagging along with scuba divers to visit offshore dive sites. We did a cave tunnel swim through, took in the colorful coral gardens, and hung out with diverse marine life including a six foot black tip reef shark. At the end of our second dive we caught a bit of luck when a 20 ft juvenile whale shark showed up to the party. The docile creature slowly milled about, mouth agape, munching on krill as we swam with it. A few scuba divers tried to keep up but their bulky gear slowed them down and because they were breathing compressed air they couldn’t change depth. Totally unfettered by these constraints, I could easily drop to 20 or 30 ft to accompany the lumbering giant. It was surreal. The rest of my time in Koh Tao was spent enjoying the island pace of life. For Daily video updates and photos follow me on instagram: @restlessben

For the freediving videos on my youtube channel please subscribe to: https://youtu.be/lOUmPtac8BA

8 Comments

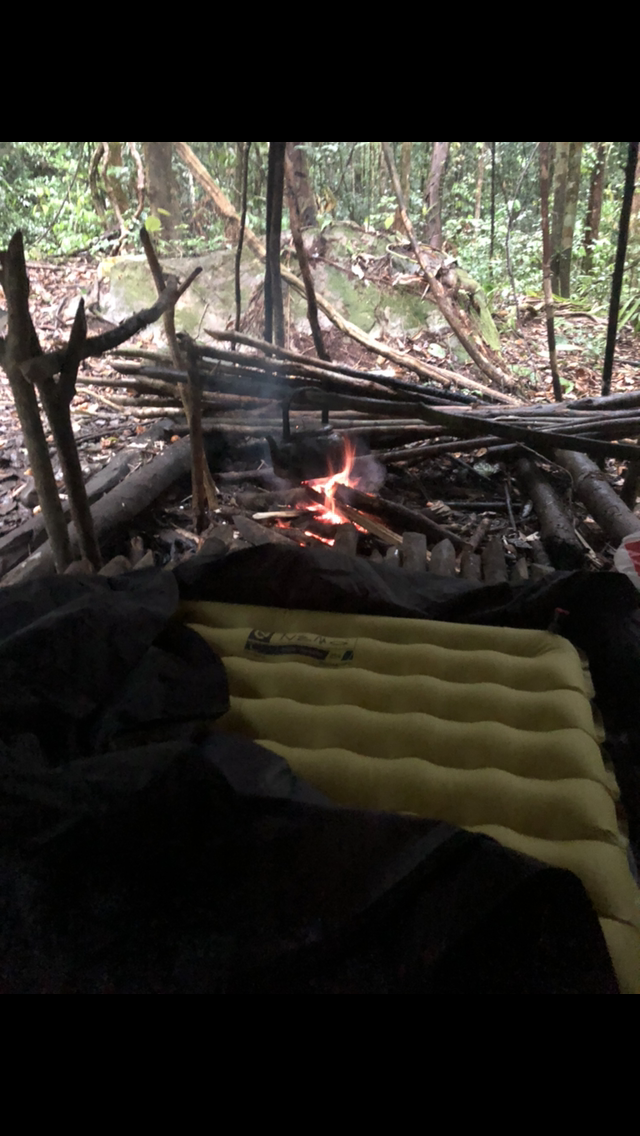

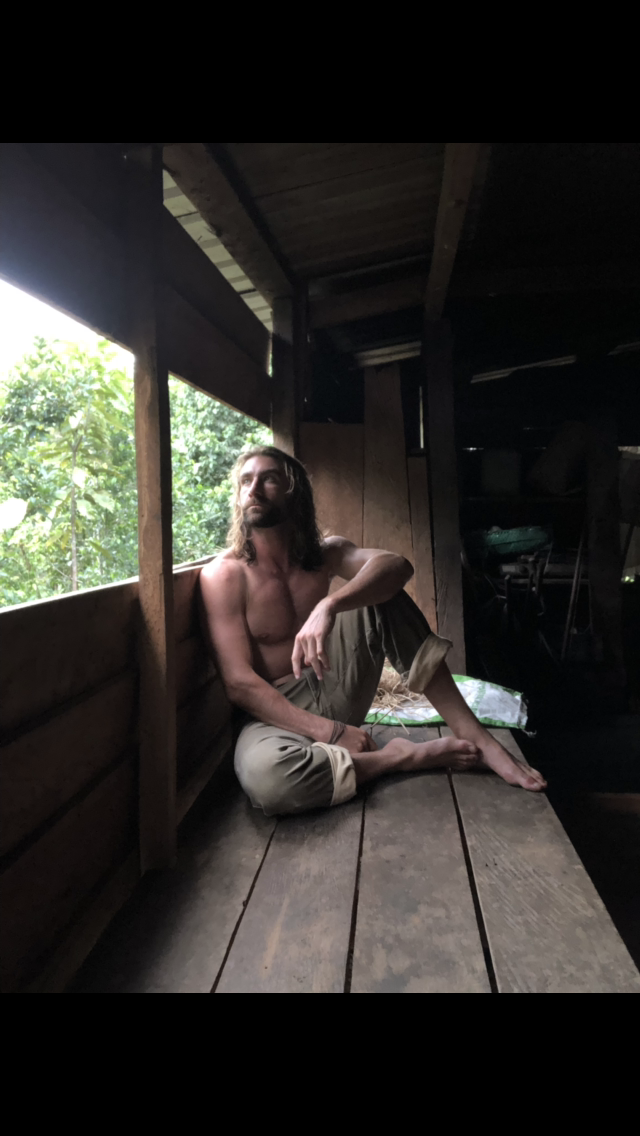

Blowgun hunting with the Penan tribe Borneo, Malaysia Fulfilling a PromiseWhen friends and colleagues would ask what I would do when I quit my job my standard response was, “I’ll be off blowgun hunting with the indigenous tribes in the rainforests of Borneo.” It seemed exotic and wild. A fun way to show my love of “off the beaten path” travel and adventure. When I started saying it, I hadn’t even realized that they still hunted with blowguns in Borneo. So when Lee Sha drew a poison dart out of his bamboo quiver, slid it into his blowgun, and shot a bird out of a tree, it was surreal. This was it. I had arrived. My new gear The Penan kit load-out includes a handmade, hardwood blowpipe with a 14” spear blade fixed to one end with a rope-like vine that hardens to industrial strengths when dry, a bamboo quiver filled with poison tipped darts, and a sheath with a machete and a smaller knife for finer jobs. In their packs they also carry a hand net to fish the thundering rainforest rivers, still teaming with life. "Sharing among the egalitarian Penan tribe is not viewed as a generous “above and beyond” gesture but is rather common place." As we hiked the narrow footpaths, Lee Sha would skillfully swing his machete to cut back the underbrush. Vegetation grows so quickly that without regular attention the path would become completely obscured in a week or two. When we passed three other Penan hunters going towards Bario, he gave each of them a cigarette to smoke and two more each for the remainder of their journey. Sharing among the egalitarian Penan tribe is not viewed as a generous “above and beyond” gesture but is rather common place. On our return journey, without being asked, two other Penan hunters on the trail would give us tobacco and some of their bracelets, woven from the same vine used to secure the spear. Extremely strong vines used in tools and bracelets Four muddy, steep, slippery, humid, leech-filled hours into the day’s hike it became evident that the brothers weren’t going to take it easy on me. We had to make it to “Bow-gow”, that night’s hunting camp, before sundown. The perpetually wet roots and rocks are all black ice to the hiker. With a full pack, slipping off balance is compounded by the shifting weight, making missteps exhausting to catch and at times extremely dangerous, especially along narrow portions with sheer drop offs. The death march Making Jungle CampAt 4:30pm, drenched in sweat, we trudged up to a clearing on top of a bluff overlooking a small waterfall. Before us was our glorious camp, an open-air, tarp-covered shelter adorned with several wild boar jaws. Rajah Lee disappeared into the forest with the fishing net while Lee Sha and I chopped wood, made the fire, and extended the shelter with a tarp from their packs. It was dusk and raining hard by the time Rajah Lee returned with 5 fish for our dinner. There was no complaining or bickering. Both brothers new what had to be done and worked almost silently in tandem. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle is very labor intensive. A significant amount of time is spent setting up camp, going to find food, catching it, preparing it, and eating it. "When the rain stopped a jungle fauna cacophony erupted." Comfortable and dry under the tarp roof with a fire at our feet, I dozed off to the sound of rain on the roof. My bedding consisted of a waterproof bivy sack with an inflatable sleeping pad. The brothers, on the other hand, slept directly on the sapling trunks of the shelter’s floor, lofted on a log a few feet off the ground, with nothing more than a thin blanket. When the rain stopped a jungle fauna cacophony erupted. The rainforest is always filled with bird and insect calls but at night it gets turned up to full blast. It sounds like someone put the “rainforest sounds” setting on their keyboard, chugged a bottle of vodka, and started violently mashing the keys. But eventually the day’s exhaustion set in and I drifted off. The second day was another jungle death march to the Penan village of Lamin on the far side of Pulong Tau National Park. We spent two nights in a Longhouse there, which was opened to us with no expectation of payment. The Dayak tribal custom is to provide lodging to anyone who comes to the village, similar to the practice of “Pashtun Wali” in Afghanistan. The village was ten longhouses with no more than 40 or 50 people, although some of the semi-nomadic inhabitants were likely off in the jungle during our stay. Penan Longhouse TraditionOnce we got settled in, Lee Sha took me visit the village chief, as is customary for all visitors. As soon as we sat down on the low, wooden stools by his longhouse hearth, the chief took several of his handwoven bracelets off and handed them to me to put on. I smiled gratefully as I slid them over my hand. During the past two days with the brothers I had developed a modest lexicon of words and phrases in the Penan dialect. It seemed like a good time to take them out for a spin. I put together a phrase that I thought was “I like Penan food” but it actually turned out to be “I like to eat Penan people” which was met with the most laughter I’ve seen from these stoic people yet. Maybe they wouldn’t take my head as a trophy after all. Two day trek from Bario is the Penan village of Lamine We spent what felt like a long time sitting there together, largely in silence. In western cultures these types of meetings are usually most comfortable when there is near constant conversation. In contrast, the Dayak are content to sit together in silence, breaking it only to share a few sentences. It was dusk and the mosquitoes were absolutely murdering me but, out of respect, I did my damnedest not to fidget. Before we left, the chief accepted my gifts of 60 RM ($15), some over-the-counter painkillers, and antibiotic cream for topical infections. "Maybe they wouldn’t take my head as a trophy after all." Giving out notebooks and pencils to the Penan children in the village The next day I gave out all of my notebooks and pencils to the Penan children, complete with custom artwork. On three separate occasions, other kids that hadn’t received one came by our longhouse to collect their booty after being tipped off by other young recipients. In the late morning, the brothers, a village boy, and I headed into the forest to go fishing and blowgun hunting for small game. During our hike to the river the young boy farted. He looked at Lee Sha and everyone burst into laughter. A Borneo tribe, that could hardly be more different from western culture, finds farts funny. This anthropological case study seems to suggest that breaking wind may in fact be universally humorous. A Penan lunch prepared in bamboo Lee Sha and Rajah Lee showed me how to get drinking water from bamboo shoot compartments and a type of thick vine, caught fish for lunch, and then cooked rice and the fish in bamboo. That evening, next to our longhouse hearth we had a delicious meal of wild boar before preparing darts and dipping them into poison for the following day’s large game hunt. Our intended targets would be boar and deer. The HuntAfter breakfast we trudged back to Bow-gow camp and took a nap. That evening a successful hunt yielded a deer, brought down with a poison dart and finished with a spear, which was promptly butchered in the stream and smoked to preserve it. The following day was spent hunting birds and small game near camp. In preparation for that night’s fire I was chopping a large log with a machete when the blade skipped up and bit deeply into the left knuckle of my index finger. I got one good look at bone and cartilage before my hand was covered in blood. Without hesitation, Rajah Lee quickly made strips of cloth from a shirt to stop the bleeding while Lee Sha boiled water and added salt to clean the wound. That night, laying in the darkness under the tarp with a throbbing hand, I thought to myself how swell it would be if I had a few of the painkillers I had given to the chief of the village a day’s hike in the opposite direction. "We had to knock on the town docs door but he graciously opened the clinic and fixed me up, tetanus shot and all." In the morning we had breakfast and broke camp for the seven hour hike back to Bario. When we finally made it back to the brother’s longhouse at the outskirts of town, I was absolutely smoked. They gave me a quiver with poison darts, some bracelets from their arms, and a handwoven game bag as parting gifts. When Ricky picked me up with a pick-up truck, I paid the brothers the $150 we had agreed upon for the six day adventure, gave them another $70 for a traditionally handmade blowgun which they procured for me, and gave them the fishing speargun I had brought along. They had been fascinated by it and I was happy to give them a gift to show my appreciation for their companionship. Using Ricky to translate, they were able to clearly communicate with me for the first time in a week of spending every waking hour together. They said they enjoyed having me along and hoped I would come back with my brother to go hunting with them again some day. I told them it had been an honor and I looked forward to our next hunt. Rajah Lee checking out the speargun I gave them, stitched hand, Penan longhouses before Bario After we got back to Nancy’s guesthouse, Ricky took me to get my hand sewn up. We had to knock on the town docs door but he graciously opened the clinic and fixed me up, tetanus shot and all. Words can’t explain how delightful it was to have a hot shower, put on clean clothes, and go to sleep in a bed. Then, as quickly as it had all begun, I was looking down from the little Twin Otter plane at the misty rainforest as I headed back to civilization. Instagram: @restlessben

Youtube channel: Restless Ben (please subscribe) This post's corresponding travel video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbQPTJU5qu8 Podcast: www.anchor.fm/restlessben Penan tribal hunters in the Borneo highland rainforest. From left to right: Two Penan hunters met on the trail, Lee Sha, Me, Rajah Lee. LeechingI felt the telltale pinch of a leech on my calf and rolled up my pants to pull it off. Too late. My leg was already covered in blood thanks to an anticoagulant the parasites excrete so they can kick back and let the good times flow. A fat little bastard fell to the ground. As judge, jury, and executioner, I saw to it that justice was meted out immediately by smashing it with a nearby rock. It exploded satisfyingly like a tiny blood-filled water balloon. By now I was no longer phased by leeches. This was the fourth day of a jungle trek with members of the indigenous Penan tribe in the highlands of Malaysian Borneo and I had begun to adjust my mindset to meet my new, austere reality. Damn leeches With no real plan in place, I did some cursory research into jumping off locations to get to the primary rainforest of central Borneo. The idea was to get as far off the grid as possible and explore the pristine rainforests that still offer a biological cornucopia like nowhere else on earth. I was also hoping to rub shoulders with some of the more remote headhunter tribes whose cultures have remained largely intact, relatively unadulterated by the pervasive modernization that has diluted other rich heritages the world over. "My leg was already covered in blood thanks to an anticoagulant the parasites excrete so they can kick back and let the good times flow." From the window of the little prop plane to Bario I could see the massive palm oil plantations, with their manicured rows extending off towards the horizon. Then, without warning, the scenery changed to dramatic mountains, blanketed in stunning primary rainforest. My face was plastered against the window for the remainder of the flight. I could not wait to go exploring deep into this breathtaking jungle wilderness. Palm oil plantation, Primary Rainforest, and Bario The Kalabit and Penan TribesBario’s airport is the size of a small restaurant and feels more like an outpost than a transportation hub. I walked out of the front and realized there were no taxis in the remote village. Thanks to the good natured, local hospitality, I was given a ride in the back of a pick-up truck to “Nancy’s Guest House.” My host Ricky, set me up in a bungalow and told me that he and his wife, who lived next door, would like to host me for dinner. The tiny town didn’t have much in the way of restaurants so I gratefully accepted. A member of the well educated and more modern Kelabit tribe of the Dayak people, Ricky and his wife spoke English well and were long time residents of Bario. With several hours before dusk, I told Ricky that I was hoping to do a grueling multi-day jungle trek. “When people come here they stay at a Kelabit longhouse and get a guided day hike to some of the surrounding hills,” he explained. “I don’t know guides that do multi-day treks.” But I didn’t want to do what the other travelers do. Getting the canned “cultural experience” of staying in a traditional Dayak longhouse, a lofted building with multiple rooms, a shared kitchen, and a communal area, here in town wasn’t going to cut it. The Kelabit, a tribe that has embraced modernization, have abandoned their hunter-gatherer, headhunter past, and remain in town, relying upon farming and other sources of income. I didn’t come all the way out here for the package deal on offer from the Kelabit guides. I brought my camping gear, I’m in decent shape, and I was ready to “embrace the suck” of a truly hardcore rainforest adventure. I wanted to get into it. Really into it. "Quickly recalibrating my own handshake pressure, I shifted from “medium” to “kitten feather tickles” to match the cultural gesture." A traditional Penan loadout: Spear/blowgun, machete, poison darts The semi-nomadic, former headhunter, Penan tribe, of the Dayak people, maintain a more traditional lifestyle, augmenting their diet with wild game which they hunt with a blowpipe. Today they cultivate rice and garden vegetables but many rely on a diet of sago, jungle fruits and hunting. Game includes wild boar, barking deer, and mouse deer as well as snakes, monkeys, birds, frogs, monitor lizards, snails and even insects such as locusts. They catch their prey using a 'kelepud' or blowpipe, made from the Belian Tree and carved out with unbelievable accuracy using a bone drill – the wood is not split, so the bore has to be extremely precise. The darts are made from the sago palm and tipped with the poisonous latex of the Tajem tree which can kill a human in a matter of minutes. For a short National Geographic documentary on making Dayak blowpipes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pJBpkz29-DQ&authuser=0 For an extensive, scholarly explanation of the poison used for the darts: http://nomadicpixel.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Blowpipe-Dart-Poison-in-Borneo.pdf Getting in with the TribeAfter reiterating what I was looking for, Ricky laughed and said, “The Penan still go hunting in the rainforest for sometimes a week at a time but they don’t speak English or have guides.” Now we were getting somewhere. “Do you know any Penan people we could talk to about me joining a few hunters heading out?” I asked, unable to contain my excitement at the prospect. Realizing that I wasn’t going to give up he relented, “We can go talk to the Penan tribal leader here in Bario if you’d like.” The Penan tribal leader was a man in his early 50s with stretched earlobes, slender but muscular arms, and a hard face that looked like it had been carved out of wood. A stoic face like his would be the last thing an enemy would see as the fatal poison of a blowgun dart coursed through their veins. Heads were previously taken by the Dayak not only show bravery in battle but also for their spiritual elements. The practice was so ingrained in the culture that young men would have to present a head in order to marry. Although headhunting in Borneo officially ended a century ago, the traditional headhunting warrior culture has not disappeared. The same blowpipes and machetes used for hunting deer and boar have been turned on people. In February 2001, Dayak tribesmen armed with spears, machetes and blowpipes roamed a market town in central Borneo killing over 200 migrants, resented for taking jobs and land. The heads of many of the dead were taken as trophies by the tribesman, whose head-hunting tradition extends back centuries. A local hospital doctor confirmed that the victims had been hacked with traditional Borneo machete called mandau or shot with poisoned darts from blowguns. (The Telegraph, 2001) Built like an aging crossfitter, a real hunter-gatherer, I expected a correspondingly powerful handshake from the Penan tribal leader across from me. But when I reached for his hand, I was given a humorously gentle grip, his fingers not even closing all the way around my hand. Quickly recalibrating my own handshake pressure, I shifted from “medium” to “kitten feather tickles” to match the cultural gesture. "Worst case scenario I get my head cut off and put up above a Dayak longhouse fireplace mantle." Base camp Bario As fate would have it, the man’s two sons were preparing to go out for a week long hunt the following morning. With Ricky translating, we were able to convince him that I would be able to make the journey. He was initially concerned and explained that the terrain was very difficult, they would be camping in the jungle for multiple days, and asked if I done this sort of thing before. After some emphatic reassurances, he gave his blessing and introduced me to his two 20 something sons, Lee Sha and Rajah Lee. They both had wirey, muscular builds, like their father. We lightly shook hands and smiled at each other in silence. Ricky looked at me, still a bit uncertain, and said, “I’ve negotiated 100RM ($25) per day and you leave from here at 8:30am tomorrow. Is that ok?” “Perfect!” I said grinning like a kid on Christmas. Holy shit. That went way better than I could have hoped. Unsure what to expect, I bought a week’s worth of canned goods and instant noodles. During dinner with Ricky and his wife Jen, conversation revolved around the next day’s trek. “You’re crazy. I’ve lived here my whole life and I’ve never done anything like this,” Ricky said, shoveling a bite of rice and chicken into his mouth. “They don’t speak any English. How are you guys going to communicate?” I smiled, “We can talk with our hands and make it work.” He shrugged, “Well, I look forward to hearing about it when you get back. I’ll drive you over at 8am.” Since I was the only guest, Ricky agreed to allow me to leave the things I didn’t bring with me in the room without paying for additional nights. Before bed, I packed my camping gear and food for the next six days. My bare bones gear load-out for the jungle trek Heading into the HinterlandsIn the morning, we met at the brother’s Penan longhouse at the edge of town as they finished packing their hand-woven backpacks. Both had the headhunter warrior physic and were armed with the full Penan loadout, machetes, spear, blowgun, and poison darts. The three of us were disappearing into the jungle for a week. Since I had abruptly lost all connectivity, I hadn’t told anyone my plan beyond going to Bario. Yet, here I was, about to accompany two complete strangers into the wilderness, members of a clan whose tribesman had ritualistically taken the heads of their murder victims when I was still in high school. Seems like a solid plan. Worst case scenario I get my head cut off and put up above a Dayak longhouse fireplace mantle. The Penan hunter's house In preparation for the village we would be visiting, I had bought some pencils and little notebooks for the children. As we waited to head out, I drew a picture in one of the notebooks and gave it, along with a pencil, to the family’s 6 year old daughter. It was a big hit. She returned the gesture, giving me a yellow headband to wear as we gently shook everyone’s hands. I promptly put it on, smiled, and tightened my backpack’s waist strap, striding behind Lee Sha into the jungle. For the full Borneo experience subscribe to my youtube channel: https://youtu.be/SAroP_9azY0

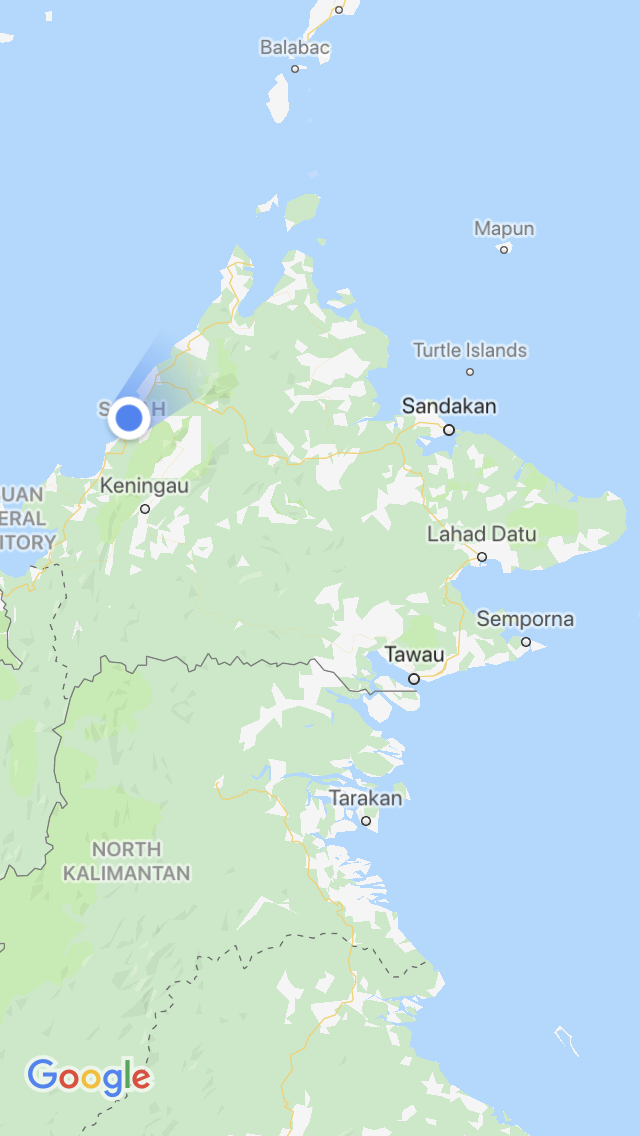

For daily videos follow me on instagram at: restlessben For the RSS feed use the link below: There were wet footprints leading to where my backpack was propped against the wall next to my bed. I could see immediately that my bag had been rummaged through. “No, no, no. Fuck, fuck, fuck”, I said to myself under my breath. A local woman sells her wares on Mabul Island, Malaysian Borneo After returning from a freediving session I had grabbed the key from the front desk of my hostel and strolled into my six bed dorm. Unlike most hostels there were no lockers to secure valuables but the dorm room was always locked and only opened for those staying in it. How could I have been so fucking careless? Schooling Jacks in Semporna, Malaysian Borneo PC: jackychan_uwphoto Digging through my bag my wallet was gone but I found my passport and backup credit cards. Ok. This sucks but we’re still in business. Then I saw my wallet laying on the ground next to my bag. “Huh. That’s weird. I’m sure the cards and cash are gone but at least I get my wallet back,” I thought to myself bitterly. Since there are no ATMs on the little island I had taken out approximately $400 to cover my expenses. This was going to hurt. I bent over and picked up my wallet. “Wait. What??!!” My cards and all of my cash were still in the wallet. This is just bizarre. Worst thieves ever. Hell yeah! After going through my bag, not a single thing was missing. I’ve racked my brain and I think that one of the other dorm inhabitants must have lost something and decided to to see if someone else in the dorm had stolen it. My little backpack with my wallet, phone, and passport was with me from then on. I even slept with a leg over it. No point in pressing my luck. A juvenile jack joined me as protection from larger fish After spending a few days taking in the wildlife in Kinabatangan National Park I had headed to the Malaysian dive destination of Semporna. Several days on Mabul island were spent freediving to the local dive sites that were conveniently located at a depth of around 60ft. Instead of paying to scuba dive I opted for the far cheaper and more exciting breath holding option. As my brother Luke aptly noted, pulling up next to scuba divers while freediving “feels like having a super power.” Why scuba dive when you can freedive instead? From an overhead view, Mabul island looks like a pin cushion with piers jutting out from every angle. Locals and dive outfits alike have built lofted villages above the water to expand the island’s limited real estate. Semporna’s natural coral and marine life is undeniably impressive but there was an alarming amount of garbage in the sea. One morning I watched a man fishing out of his living room for his breakfast as a freshly discarded baby diaper floated by. It was a jarring image. Better education and waste management will be crucial where natural treasures are threatened by human activity. Hopefully humanity can figure out a way to curb population growth and find a sustainable coexistence with our environment before it’s too late. To get to the heart of Borneo I found out that I would have to make my way to Miri, which hosts the only airport in Malaysia flying to the rainforest highland town of Bario. The 12-seater “Twin Otter” prop plane which makes the flight, looks out of place next to other, normal sized passenger planes on the tarmac. As the crow flies, I was closer to Bario from Semporna than Miri, which is on the opposite side of the massive island, but since I can’t ride a crow, I got moving. From Semporna I took a series of boats, buses, and flights from the eastern coast of Malaysian Borneo to the western coastal town of Miri where I could be spirited off to the rainforest hinterlands. For full videos subscribe to my youtube channel at: https://youtu.be/SAroP_9azY0 For daily videos follow me on instagram at: restlessben |

AuthorBen quit his job to travel the world. He intends to keep winging it as long as he can. Archives

April 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed